The first bandstands can be traced back to the latter half of the eighteenth century when fanciful pleasure domes were erected to house orchestras, and in some cases dancers too, amidst rambling gardens set out to delight the eye and provide vistas for the visiting crowds.

One of the earliest bandstands to have been built was in London's Vauxhall Gardens, while the first specifically built for bands was in Cremorne Gardens, also in London: there bands provided a glittering spectacle in an illuminated pagoda, which offered a perfect focal point for the many entertainment's. The first bandstands were greatly influenced by oriental architecture. Since Sir

William Chambers, a prominent l8th century architect, constructed his famous Chinese tower at Kew in 1762, the pagoda had become a traditional building in English parks and gardens. Chambers was an enthusiast for all things Chinese: Chinese buildings he thought unremarkable for magnitude or richness of materials but he admired their proportions, simplicity and beauty. He also drew attention to the Chinese emphasis on the importance of a building's precise location and he stressed the need to site a bandstand where its features would be displayed to the best effect .

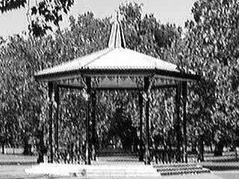

These ideas proved to be an inspiration to Victorian designers who were commissioned to create islands of nature in the midst of industry. As Victorian entrepreneurs urbanised the landscape, building terrace upon terrace, mills and factories, the lack of access to fresh air and pleasant surroundings became a serious health and social problem. The Victorian solution was to create parks and gardens. Burgesses, reformers and often developers themselves made land available, often on condition that the parks were named after them. West Bromwich opened its 56 acre Dartmouth Park in 1878 on the instigation of the Improvement Commissioners, the land being leased from the Earl of Dartmouth. Once parks were established the people using them soon sought entertainment. Bands, being well suited to open-air entertainment, soon found

themselves with very full programmes, and never more so than in what became known as the 'summer season'. Larger industrial towns often provided several bandstands, especially in the Black Country , where a long tradition of iron- founding reduced the cost of fabrication. West Bromwich's first bandstand was opened in 1887 in Dartmouth Park. It housed bands on two afternoons a week and there was a 'sacred' music concert on Sundays. In 1897 a second bandstand was opened at Hill Top by the Mayor and Samuel Downing, a local ironmaster who doubtless bore a proportion of the £160 building costs. At nearby Wednesbury , where a park was opened to celebrate Queen Victoria's Jubilee, the bandstand figured prominently until as late as the 1953 coronation celebrations when Shirley Prize Band, Keith Hampton and his Castle Rock Orchestra and Harry Engleman and his BBC Playersoffered an astonishing variety of music. In the late nineteenth century bandstands were in such great demand that ironmakers included them in their catalogues. To some extent this led to a standardisation of styles as there was inevitably a limit to the variations possible with ready- made kits. At the same time some customers preferred to put the building of their bandstand out to competition. Some commissioned distinguished architects, for whom the design of a bandstand must have been something of a diversion. Captain Fowkes, architect of the Albert Hall in London, is known to have designed two bandstands for erection in the Royal Horticultural Society's grounds in Kensington in the 1860's. One of them was later moved to Clapham Common, where it has been used ever since. Some customers wanted something a little eccentric and a flight of municipal fancy seems to have been favoured in many seaside towns. Southend's bandstand, for example, was a monolithic extravagance adorned with classical urns, garlands and foliage, all encased by glass screens and topped by a large globe, itself surmounted by a pointed turret .

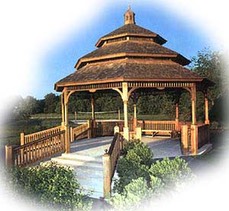

At Bournemouth, a resort with a long musical tradition, four bandstands were built for bands and other entertainment's. For promenaders using the pier Bournemouth once had a fine Chinese-style stand at its pier head. Here crowds sat on benches beneath flapping canvas awnings, as Captain Featherstone conducted Bournemouth's Municipal Band or while the Municipal Orchestra played selections from its concert repertoire.

In the town's Lower Pleasure Gardens stood another stand, a rustic piece with a thatched roof. Bournemouth's two other bandstands were constructed later, on public walks: Fisherman' s Walk and Pine Walk. The latter, erected in 1933, took the form of a huge wooden square measuring 22 by 25 feet (6.7 by 7.6 m), complete with four sets of sliding and folding windows.

In the heyday of the British Empire bandstands spread from one end of the world to the other; bandstands were built in Valparaiso, Nassau, Monte Carlo, Milan, Poona and Calcutta. Wherever the British went, whether for business or pleasure, bandstands were sure to follow.

There was no restriction on style. Some were strictly utilitarian: others rose in cakestand layers and Japanese frills. And the popularity of band music all over the world led to a multiplication of stands in parks and gardens in countries with highly individualistic architectural traditions, a factor which further enriched the diversity of styles already introduced by British designers.

Though bandstands are one of the more curious products of English architecture there can be few buildings which span so many countries and exhibit such a variety of architectural styles.